XÓCHITL GARCIA

CONNECTICUT

Xóchitl has been working on farms since 2020. She is the director and founder of Turtle Island Steward Collective.

This interview was conducted by Mallika Singh.

Can you tell me a little bit about yourself and what you're currently doing, where you're working, how long you've been working on farms?

So my story is a bit complex. I started farming in 2020, a month after the government shutdown in Connecticut. I entered into urban farming, to be specific, because I needed income. I was unemployed for almost a year because my first full time job fired me the first month that they onboarded me because they over hired me and other personal stuff they would never admit to. Long story short, I think that was a blessing in disguise, because going and feeding my community has allowed me to explore the meaning of community, but also how important it is to develop micro-structures to kind of detach from Big Ag, and also being of service to people. Because often when we think of service based jobs we think of telephone centers, or people who are processing your insurance, but no one really thinks of farming as a social service.

I think it's because we take it for granted. We are an invisible labor force. That is just providing this constant churning of sustenance. I was able to see that whole system and then have a conversation and connection. That made it very meaningful for me, and so I've been able to explore other sectors of food systems like serving as an advisor, a consultant, even project lead on certain things. The most notable one that I'm currently in is as a farm based wellness coordinator at a nonprofit where, essentially, I'm providing a life intervention summer long course for people who are at risk for diabetes and high blood pressure. We collaborate by exposing them to micro farming at one of our plots, and then understanding the importance of consuming local but more just consuming fresher food and supplementing them with anywhere between 10-15 pounds per week during the program course.

Also having a lot of conversation about what health means and decolonizing the food palette. We're often stigmatizing our own cultural foods and adhering to the white palette without questioning how that affects our well being and connection to our roots. A lot of people in this program are from other countries, like Mexico, Iran, really a lot of different places. So we want to make sure the food being grown is something they would eat at home and that could be shared. We're creating a system in which they're understanding farm to table, but also farm to community, farm to family.

How did you choose to work on an urban farm? I know you said you were looking for work, but did you have any kind of inclination towards it before? Did you have an idea of what working on a farm would be like?

I had stories that were told by my parents, and that was because to them, farming was a form of survival. So when they did provide stories, it was more of a struggle, the amount of hay or food that they had to haul for bigger livestock, like cows and horses, and being injured by them at the same time. So that experience made farming very aversive, and in some way it was an internalized classism of seeing farming as an inferior job. When I delved into that field, and then let my parents know after the fact, they were more shocked, because they were like, you went to college to study a double major in urban and environmental studies…just so you can settle on farming? It was a bit of a tension for them to accept my position, but over time, it served as a way to connect our stories. For example, I was fascinated by how there could be a vine of tomatoes, but all of them have a spectrum of colors, from green to red. For me that was very new, but to them, it's obvious, because they started telling me about the sun and the way the leaves cover and how that affects photosynthesis. They didn't use the words photosynthesis per se, but we were able to understand each other despite having kind of like an educational barrier, but we knew what we were saying to one another and enjoying that food in between our conversations.

I've heard similar stories from a lot of people whose parents or grandparents were farmworkers or farmers as their livelihood. When their kids get into farming, they're like, why would you do that? This is not why we sent you to college. But then sometimes families end up connecting over it too, which is really cool. So, how long has it been that you've been farming?

Since 2020, it's been off and on, especially after 2022 because I worked at a nonprofit farm, and I recognized a little too late into my third year that I was being severely underpaid. In Connecticut, it was $16 an hour. But considering that I was working multiple roles – I was a program assistant volunteer coordinator as well — it was just too much at once for $16 an hour. And luckily, I had the privilege to live with my parents, but I came to a point where I was trying to be independent. So I fully transitioned out from farming, but then resumed it a couple years later, now with the wellness program. I consider myself a farm enthusiast, but I'm also kind of a farmer again. It's kind of hard to put absolute words to this current chapter of my life. However, I think farming is now a core, core role in my life, because I have a better understanding more on the systems perspective, because some of the projects that I'm currently on are more related to improving accessibility to fresh foods, because Connecticut has one of the worst food insecurity rates in the state, and it's definitely by design from the system. We have one Ivy League school, Yale University, and then we have four other colleges, but Yale is the biggest culprit in monopolizing a lot of the land. Limited land means you can't grow much, and I would say 99% of all soil in New Haven is contaminated, because it was once a very industrial city. So people who do know how to grow need raised beds no matter what. Okay, if it's not a raised bed, at least you have to put topsoil over plastic, which is kind of ironic with microplastics – but still, you gotta try to choose your lesser evil in that sense. And so it really limits your options. You have to know someone who knows how to do this stuff or contact someone, and just even accessing those resources is a bit difficult.

Woah. I didn't know that about the soil in that area. What issues have you faced when you've been working on someone else's farm? And since it sounds like you've worked specifically at nonprofits, if you find any particular difficulties working at nonprofit farms.

My biggest issue is the community outreach and engagement that is conducted in specific neighborhoods. Where we were, most of our farms existed in a Latino neighborhood. Anywhere between 50 to 70% of people from Puerto Rico, Mexico, Central America, South America, and many of them are immigrants, so you can kind of get a sense of the foods that they eat versus the stuff that was grown at the farm. We have chard, kale, which is healthy, but it's not culturally relevant to the people growing there. On top of that, management was very aversive towards outreach in general, because they were focused more on production, even though it was a neighborhood farm, and they tried to advertise it, but there is never a visible sign that says, welcome all volunteers – nothing that gave a message to the people.

And I brought that up multiple times. Why aren't we growing corn? Oh, it takes up too much space. Why aren’t we growing beans? Well, we need a lot of rows. There was always an excuse. Where something like swiss chard was being overgrown and no one would buy it. So I think there was an illusion to grow an abundance of things but not be able to sell everything. And then there was an ego boost when we could donate these produce to food banks. We don't even know if that was even used, because people accept it if it's already pre-packaged, or it's just left alone, if it's not picked from a bin. So that tail end, I'll never know, but just seeing from the market, that product was ignored unless it was white folks. And even then, they would just pick one or two bunches because they were a small family.

There’s only so much chard you can eat!

Exactly! So that made me angry, and on top of that too, there's been so much change in management, and as a result, that also changes the relationships people have to the space. Because if you have a trusted person in a designated farm, they look forward to coming. They want to volunteer consistently, or just come and say hi, which, in a way, creates almost like a safety bubble, because where we were located, it was pretty drug infested, and there's prostitution, and so that was a deterrent for those who were unfamiliar to the farm to even go in, but those who lived literally across the street from the farm just didn't know because it was fenced off in a way that made it seem like a private farm. There were these illusions and perceptions that affected the community basis of the farm, and I vocalized that, asking how we can make it more appealing. It starts from picking up the trash, getting volunteers to do more specific roles and my ideas just never clicked to them. There's many reasons why, one of them being that management at the time was run by a man who was very sexist, xenophobic, racist, and that really bothered me and the staff, because we were staff of all women at the time, and then we hired on a male Executive Director, and then he essentially made us all gradually quit. We were twelve and it went down to three in less than two years. I even wrote a five page, single spaced letter to the board explaining what had happened, how this affected me, how this affected others. What does this mean and feel to me? There was never a follow up on that damn so those injustices themselves is why I exited out completely, but I'm back again at a much different capacity. At the same time I got two and a half times more pay, the executive director, fired, okay, he resigned.

The only reason I'm back is I know my limits now, and I started my own collective to address the gaps that are going on.

I would say, what keeps me coming back? It's a very sensory, stimulating environment, like the fuzziness of all the tomato vines, the greenness, the smell of petrichor after rain. So much is happening simultaneously. And I think growing up, people in general in America, we are so accustomed to ignoring our surroundings and just focus on what we're producing. And in a sense, farming is a type of production. But there's so many relationships going on, whether it's with the land, with yourself, with other people.

Does the farm sell the food they grow, donate it, a combination?

When we had a designated farmer, we would do both. Now we don't have a farm manager, and it’s run by a cooperative, and I have no idea what they do with what’s growing. Within the wellness program, we do more micro farming and gardening, at a much smaller scale.

Do you want to talk a little bit about the collective that you mentioned?

Yeah sure! It feels a little weird saying this out loud, because I just established this back in early November. I'm the director and founder of Turtle Island Steward Collective, and the focus is on food and land stewardship. When we think of the environment, we think of nature or climate change. And when we think about food, it's either insecurity or consumption, but they all go hand in hand. You can't have healthy foods without healthy soil, and vice versa. And I want to intersect those ideas, to introduce a lot of projects in the future for the community and to offer opportunities for people to understand what they can do within their control with support of grants or people who have direct connections with those influences like myself. I wouldn't call myself a super powerful person in the sense where, I can write my name and a million dollars comes through. It's not like that, but more that I have access to networks that have the resources that can be reallocated in our direction. Most of the people that I've worked with in the past, English is their second language, or they had formal education till high school, or just other factors that prevent them from being in these spaces. I want them to be aware and feel empowered.

A more specific project that I'm working on is river cleanups and a simultaneous community breakfast. It sounds a bit ambitious, because I want the community breakfast to have locally sourced ingredients that can be consumed on the day that we do cleanup. So the rule would be, you get a bag, spend 15 minutes, get a plate of food and maybe some extra stuff, like mutual aid resources. The river cleanup also addresses water pollution and water management, and people get exposed to the local waterways that are in New Haven. When we think of nature, we tend to think of national parks – big things disconnected from everyday experiences. So really creating these micro hubs to get people outside and to enjoy amongst each other.

I'm personally obsessed with rivers. So I would come to the river cleanup! Do you have a vision of or qualities you would want in a dream farm, not related to ownership? I think you started talking about this when describing the collective.

Absolutely. I’ve thought about it for years. I want to have a farm that functions like an oasis. There's a big plot of land with a couple greenhouses and a large tool shed. I'm giving you details.

Go for it!

I really want to focus more on plant based food, such as herbs, vegetables, and fruits. One of the things I'm recognizing that I need is anti-inflammatory foods. Recognizing how much food affects my system and how systems affect people, I kind of just want to connect the dots. And having an educational hub would be one of those cool things, where we can harvest whatever is growing for the season, and make a dish or a snack out of that. Invite people to facilitate. One of the things I've learned as an organizer is that I want to carry all of these hats, but I end up exhausted once everything's done. So kind of just outsourcing people, I think, really increases the bonding between communities. Aside from the educational portion, I also want to be able to create a market which I would advertise as something that's more Spanish language friendly, because when we think of the farmers market, it's very synonymous to white culture. In reality, it's just a market of food, but it's kind of like jacked up prices, which I get, I'm affected by that too. But if we were to just have food that was subsidized in price, or offered at a sliding scale, and we can use words like mercado, which literally means market, so people can feel welcome before they even step in. That's what's really important to me for this dream farm.

What is your take on the difference, if any, between a farmer and a farm worker or farm employee? Do you call yourself a farmer? Do you call yourself a farm worker? Why or why not?

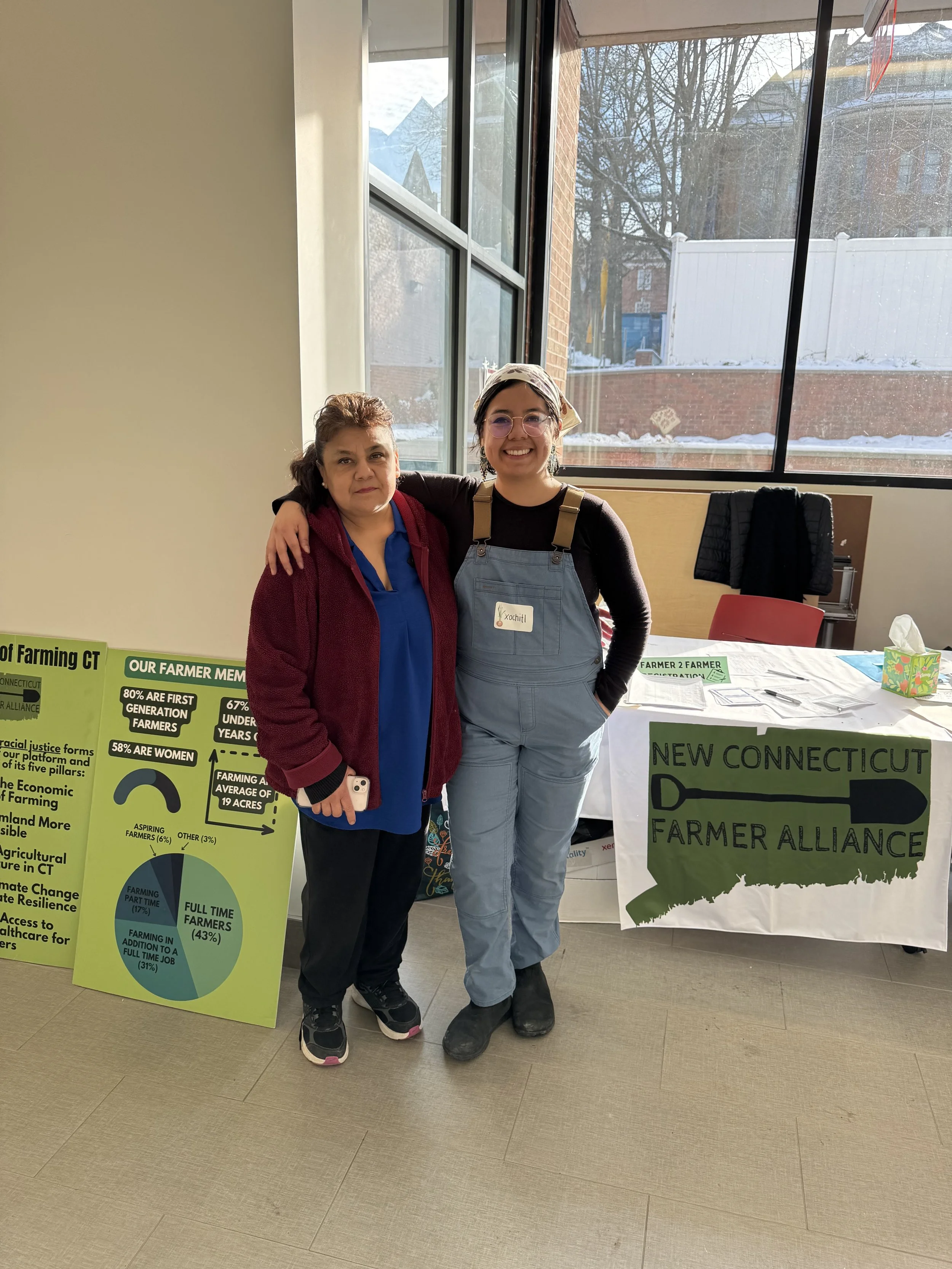

They're synonymous. I'm part of the steering committee called New Connecticut Farmers Alliance, and we went over more or less defining, maybe not formally, because I don't know if it got written out, but we had a very formal conversation, because when we were conducting a survey to our members, we wanted to assess their perceptions of certain value. For instance, would a farm worker appreciate a labor rights advocacy class versus a farm owner? And what would that mean in terms of funding these resources and providing them to the public? That was really hard, because some people said a farmer is a farmer regardless. But we also have to think about power dynamics. What if this farm owner is exploitative, and when their workers are being educated, they see that as a threat? They might censor that out, they won’t forward the listserv to their workers, because farm owners are worried their workers may want to quit, maybe they will advocate for something different, right?

I would say farmer and farm worker are the same to me, while farm owner is more about the capacity in which they're operating and running independently, and also for tax status.

I refer to myself more as a farmer. I don't really care about adding the worker because, one, it's more of a mouthful, and also, just because, and someone said something very powerful earlier this morning. I'm trying to refresh. But farm workers are often in some way, it's like a capitalistic form of slavery. Because of all farm wages, I've seen farm worker wages, it's either at state minimum wage and sometimes even lower. I had the privilege, over the summer, to work with several 100 farmers where we processed the $600 check that was provided from PASA. They all provided their W2s, and on average, a lot of them made less than $30,000 a year totally. Meanwhile, I saw that American born farmers, I mean, they didn’t make significantly more, but there was a difference in pay. I wonder if their wages are even discussed, because some of these migrant workers said they've been here from the 70s and 80s. They're as old as my parents. To know that they probably never had a wage raise, maybe gradually, incrementally, but nothing that would make them thrive. So that's where I started, noticing the importance of distinguishing owner and worker. It highlights the disparities between them and the way that they show up in a public setting, because a lot of migrant workers, and also American farm workers, were very humble in the whole process, like they were very transparent about their pay and their families. I never even asked these questions. I was just asked for an ID and W2. I think it was their first time they've had a more one on one connection, where someone is dedicating between 10-20 minutes to this process with them. They just wanted to talk, and it made me realize the importance of farmer policy and advocacy and all of the social services and acts that need to be done to support these farmers.

I like what you said about highlighting the difference between owner and worker, and also the differences between workers. You started getting into this, but what kind of support do you think would be helpful for people who are working on farms that they do not own?

I would say the first thing is see what local farming chapters are out there. One of the things I learned pretty quickly is that if you're not connected to a listserv, your world will look very small, especially if you have a small farm crew. And you also get to understand the legislation going on, opportunities, surveys for improvement. I've been super lucky that up until recently, the former coordinator of the New Connecticut Farmer Alliance would contract me several times for different projects. For instance, one of them was like translating surveys, doing survey analysis, doing different outreach, and event planning. Working at these different capacities has allowed me to understand how I better show up for farmers, but from behind the scenes. For instance, when we were designing that survey that I mentioned to you earlier, we had to be very mindful of wording like we wanted to stay neutral. But at the same time, there was a sense of political activist undertones, and we knew we were going to some farmers, especially when we said, did you know we offer bi pop service provider, etc, etc. And then I forget it was an open ended question, or multiple choice, whatever. But it was one of those things which like, well, I'm colored purple. What? What do I qualify for? And I'm just like, Oh, get real right now. There were people who want to take it seriously, but recognize the few people that did answer were very thankful, and they were very detailed, and some of the incidences that they had experienced related to discrimination, racism, etc, or simply saying that we need more of this content that is publicly available, that people can see, regardless of the status quo in a predominantly white field.

When you started farming, how did you get to know about those resources?

I actually had a coworker who was very politically active, and she was in the same steering committee. She was stepping down that year, so she invited me to fill in. That was the only way I knew about it.

What's your opinion on the farmer lunch? Do you take lunch with your coworkers? Do you skip lunch? Do you enjoy taking lunch?

Oh, goodness, goodness.I think it really depends. Depends on management. And how you prioritize your lunch. When I first started, the first two years, my manager was very insistent on you gotta get everything done by this time. She came from commercial farming, straight to nonprofit. So in a way, she was projecting that kind of energy to us.

I get you, wanting to be efficient.

Yeah. She was full time, I was part time, so it was just two people. Literally everyone else was a volunteer. Our volunteer cohort was inconsistent, so whenever they didn't show up or they canceled, I would have to pick up the slack. So I would purposely miss lunch because I was wanting to get it done. This constant thing of never ending tasks made me neglect my own nourishment. Sometimes it would be really hot or wet, which made it hard to pack food. There was never a gazebo or tent, there was a greenhouse, but that was broken. We also didn't have access to a bathroom which made things more complicated. I would time when and what I would eat, or even just getting my period was complicated. Everything had to be repressed. When she left and was replaced by someone else, he was so lacking to the point where he didn't meet certain percentages of last year. It was also a learning curve. He was more of a homestead gardener managing six farms at the same time, which was collectively maybe one and a half acres, but they were spread out through New Haven. They were all divided up. Which took time to just get across from plot to plot. Because he's a very chill guy, it was more, finish when you can, if you want to clock out earlier you can. It was just such a different pace, and I wasn't used to it. In fact, I would get mad at him. I was like, where's the rush? Where's the adrenaline?

The lack of bathroom access is such a common experience. And of course it affects if, when, how you can eat. Is there anything else you want to share about your relationship with farming, is there anything that you find yourself coming back to?

I would say, what keeps me coming back? It's a very sensory, stimulating environment, like the fuzziness of all the tomato vines, the greenness, the smell of petrichor after rain. So much is happening simultaneously. And I think growing up, people in general in America, we are so accustomed to ignoring our surroundings and just focus on what we're producing. And in a sense, farming is a type of production. But there's so many relationships going on, whether it's with the land, with yourself, with other people. I'm a very introspective person, so I’m observing everything. One of my favorite stories I like to tell is when I became more aware of how nature protects me. I used to have this American robin that would visit me every day, Monday through Saturday, in the same little plot, and at first I thought they were coming for worms. But then they would come on days where the ground is pretty dry, not going to really find much worms. And he would, I don't know…the bird kept noticing me. The only reason I noticed is because he would hop and turn around, and we both give each other this look, and then at some point, he would just fly up, but he would find his spot every morning to come see me.

Oh, he was your friend!

Yeah, that's so sweet, so cute, and you just don't get that when you're in a damn office all day.

Thanks so much for talking with me!